A People’s Museum

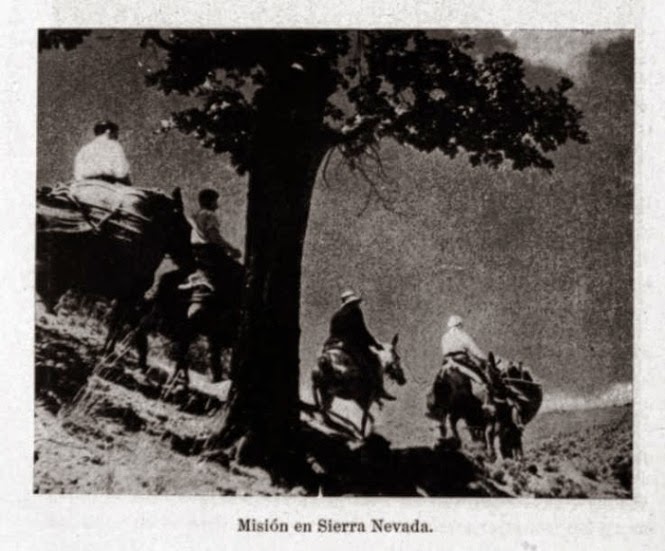

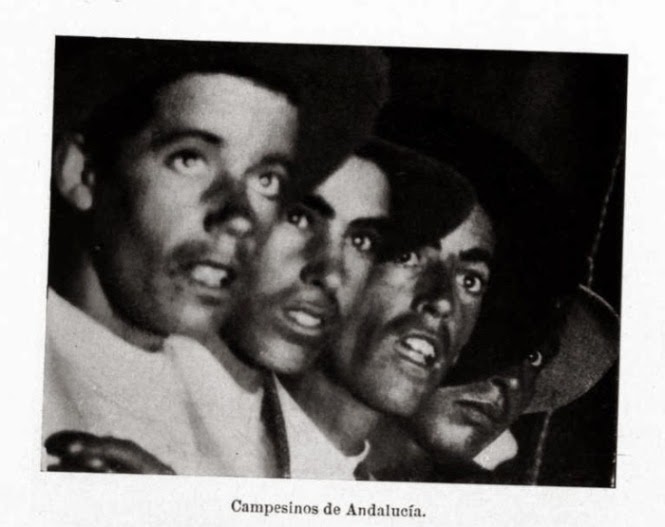

Photo: Andalusian peasants

All the characters on the canvas were looking at him, José. He could not stop shifting his eyes from right to left, from one face to another. Each one of them inspired a different feeling in him. Sweetness, intrigue, repulsion. There were also paintings inside the painting, a nun and even a dog. José felt the movement of people around him, especially children, some shouting at him to go out and play, but his gaze was fixed on the gentleman in the background, the one with one leg on the step, beyond the doorjamb, with his arm on a wall covered with a curtain. Where was he going? Why wasn’t he posing with the rest of the family?

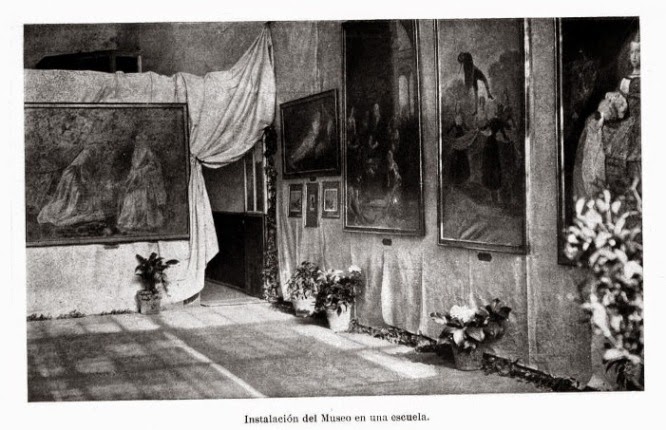

It was almost two o’clock in the afternoon and José had not moved from that hall all morning. He had quickly glanced at the rest of the paintings, but he had been in front of this one for quite some time. The strangers who had brought the paintings began to close the shutters of the room: they were going to eat.

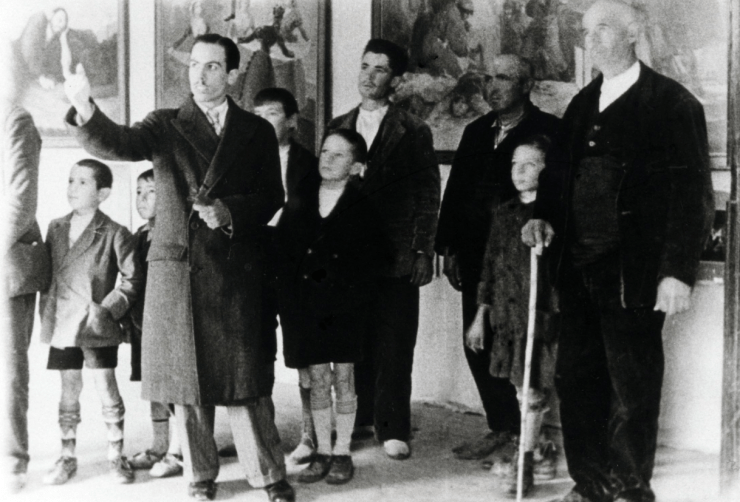

An elegant gentleman with a moustache and a long coat approached José. He was sitting cross-legged on the floor, twisting his head and frowning as he tried to decipher the large, dark painting that stood at the back of the room where the scene was taking place, on the right.

– Do you like the painting?

– Yes, but what is the painter painting?

– Nobody knows for sure. Some say he is painting the same scene, Infanta Margarita and the Meninas; others say he is painting us, the observers of the painting, because Velázquez was ahead of his time. Do you see the mirror in the background, where the man and the woman are? They are the king and queen. It is also said that Velázquez could be painting their portrait, which is why they are reflected in the mirror.

– I don’t think he’s painting anything, I think it is to make himself look interesting.

The gentleman laughed to himself. He asked him if he liked the other paintings in the exhibition. José had seen them quite quickly, so he couldn’t answer that question honestly, and he knew that questions should only be answered honestly.

Silence.

– Wow, does that mean you don’t like the others or that this is your favourite?

– That this one is my favourite. The dog reminds me of the one in the Munuera cortijo. But that one is lame, the one in the painting seems tamer, because he’s being kicked and he doesn’t get angry.

The man with the moustache laughed again. He told him that this painting was one of the masterpieces in the history of art, but that there were many others in the room that were worth seeing. He explained to José that they were reproductions from Museo del Prado, which was in Madrid, and that the originals were real treasures and, if they were ever sold, would cost a fortune.

They stopped in front of a darker painting and José immediately said that it was not by the same painter. The boy crossed his legs and clasped his hands together while making disapproving gestures with his mouth.

– Why did this painter have to paint dead people, and the one in white, who looks terrified? The paintings have to be beautiful, because if you’re going to put them in your house, how can you have one like that with blood and dead people and soldiers.

– Goya painted this because it was an important moment in our history. The French shot many people in Madrid who were protesting against the French invasion on 3 May 1808, and we must remember this so that we don’t forget it. Besides, these paintings are in a museum, and there are people who like to have them in their homes. There can also be beauty in death and blood, even if you don’t understand it now. Let’s look at the next one.

Joseph’s eyes grew wide. He took a step back when they reached the painting in the corner of the room. He hadn’t seen it before because there were so many people crowding in front of it, and they had put up a black curtained screen on one side of the painting.

– Saturn Devouring His Son. I know it’s impressive, but don’t be afraid. It is an allegory of the passage of time.

The gentleman saw José frown again, and realised that he couldn’t use that language with the boy.

– What I mean is that what you see in the painting is not real. It’s like a story the Greeks invented a long, long time ago to explain how time goes by and we grow old against our will, even if we don’t want to.

– Ramón! Ramón! Let’s eat, take the child out and then later, if you want, you can go on explaining. There’s a woman looking for her son in the square, maybe he’s the one she’s looking for – said a lady from the entrance door.

– You heard him, is that you, José? He asked the boy.

– Yes, it’s me. My mother is going to kill me.

– Go on, run. Then you can come again. We’ll be here until next Friday.

José went every afternoon after school to see Las Meninas. He closed his eyes and imagined what the painter could be up to with that great canvas. He never again peeked behind the curtain where the man who ate up time was.

On the day of his departure, José shook hands with Ramón, the man with the moustache, who was also a painter, by the way. The man took a miniature copy of José’s favourite painting out of his elegant coat pocket and handed it to him.

– This is for you, to always remember us and the People’s Museum, and so that you will find in Velázquez’s art a little of the meaning of life.

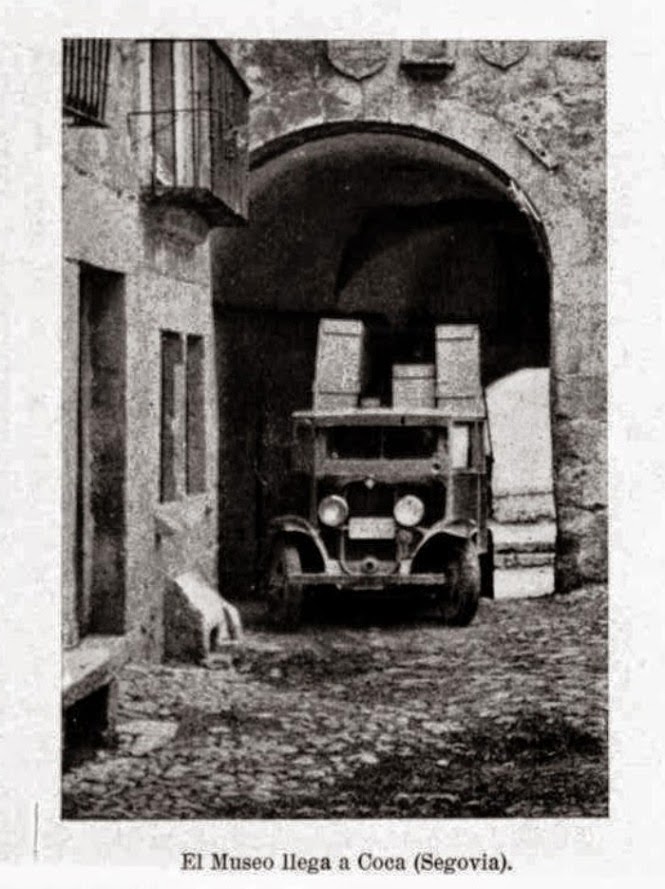

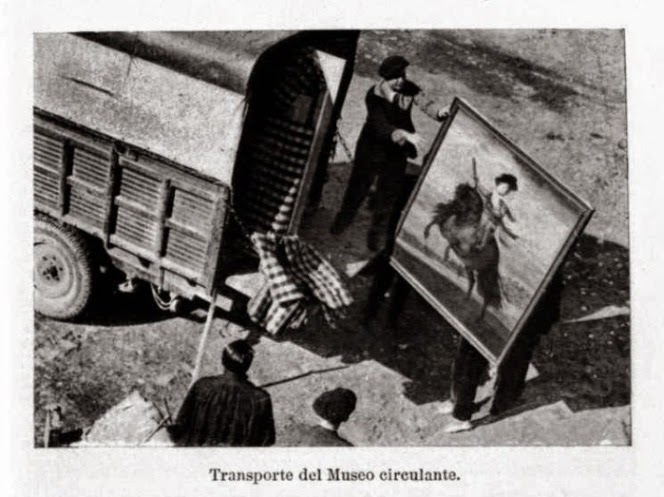

José saw them leave Purchena in the old van full of grey boxes, briefcases and travel bags.

Mr Ramón, whose surname was Gaya, continued his didactic and pedagogical journey to other towns in the province of Almería and Murcia. He travelled with his companions the poet Luis Cernuda, the philosopher and essayist María Zambrano, the writer, poet and journalist Antonio Sánchez Barbudo and the writer Rafael Dieste.

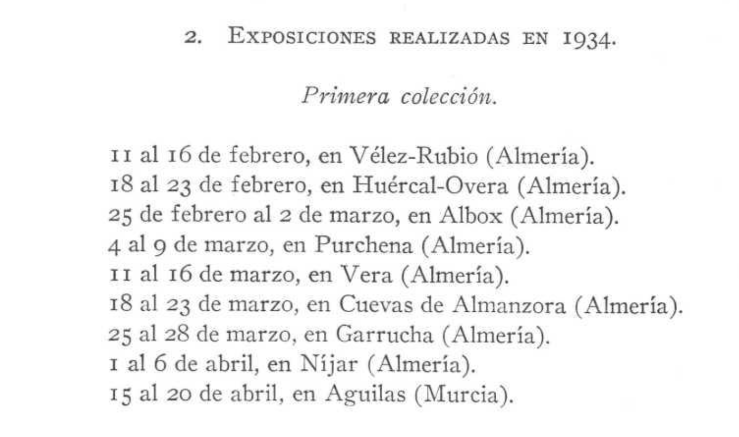

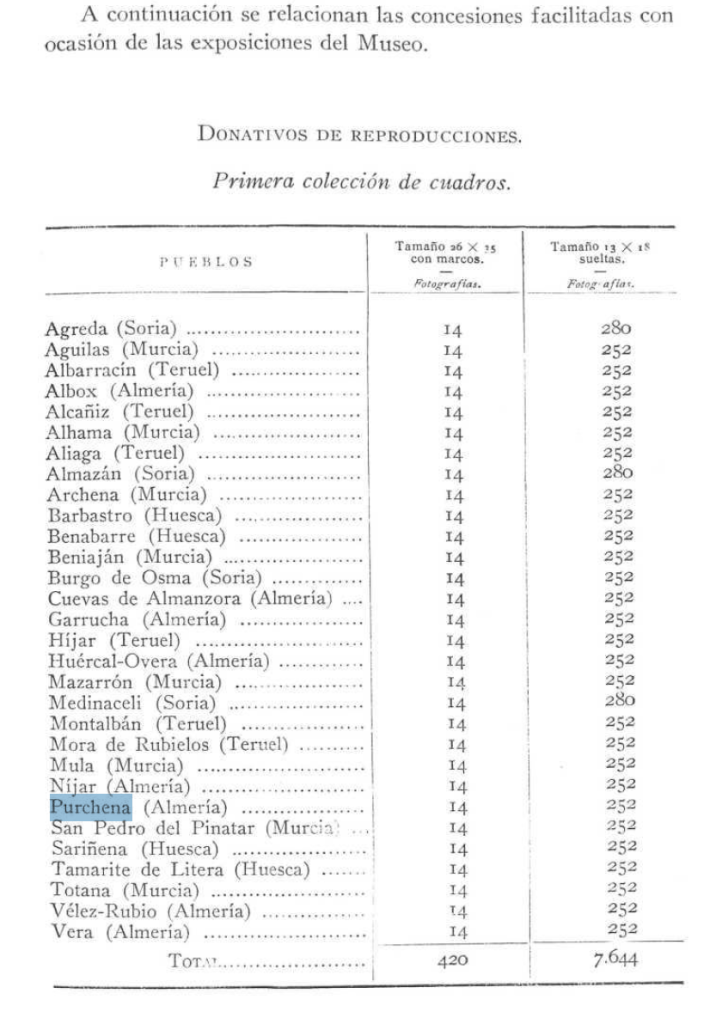

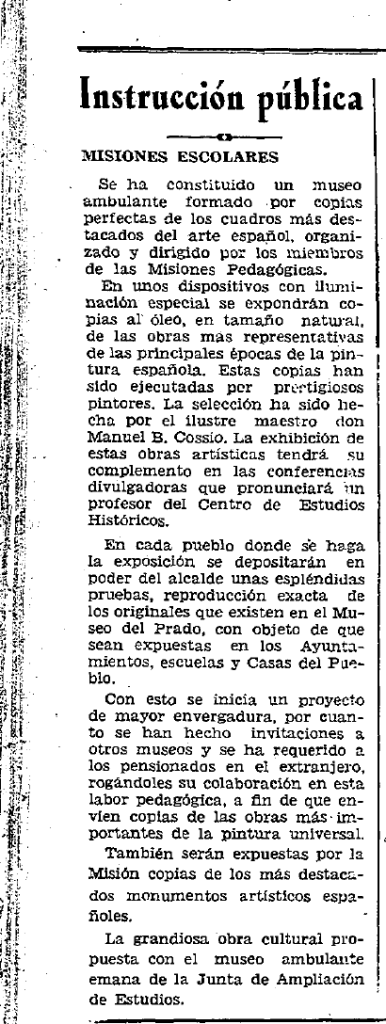

The exhibition of the Museo del Pueblo, also known as the Museo Circulante or Museo Ambulante, was in Purchena from 4 to 9 March 1934, bringing art to the most isolated rural areas at the time, with the conviction that culture is universal. This initiative was part of the Pedagogical Missions, launched by the government of the Second Spanish Republic. The Pedagogical Missions were a project of cultural solidarity that also took theatrical performances, film screenings, choirs, puppet shows, courses for teachers and the opening of libraries, among other activities, to the villages.

Author’s note: not all the reproductions of the paintings mentioned in this story were actually exhibited, although some by the same painters were, such as Velázquez’s Las hilanderas and Goya’s El 3 de mayo en Madrid (also known as Los fusilamientos).