Butter children

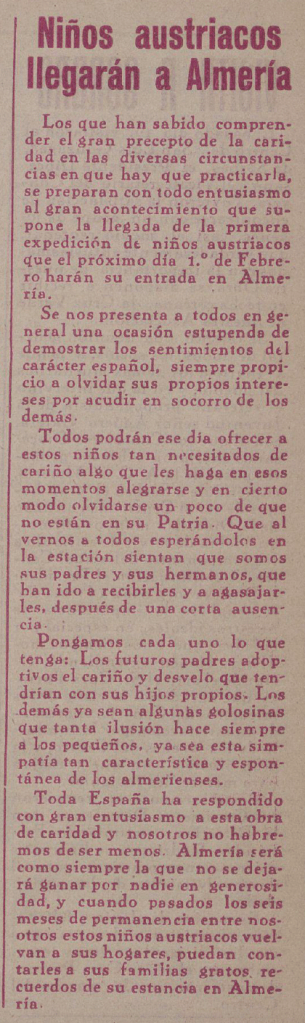

At 8 a.m. on 8 January 1950, the seventh British military convoy, carrying Hans and 498 other children, left Vienna for Spain. They would spend some time there, to recuperate and eat better, they were told, and to forget a little about the skeletal buildings that still stood in their city and most of their country.

A few days before, at school, they had been given a medical check-up and given some injections that they said were called vaccinations.

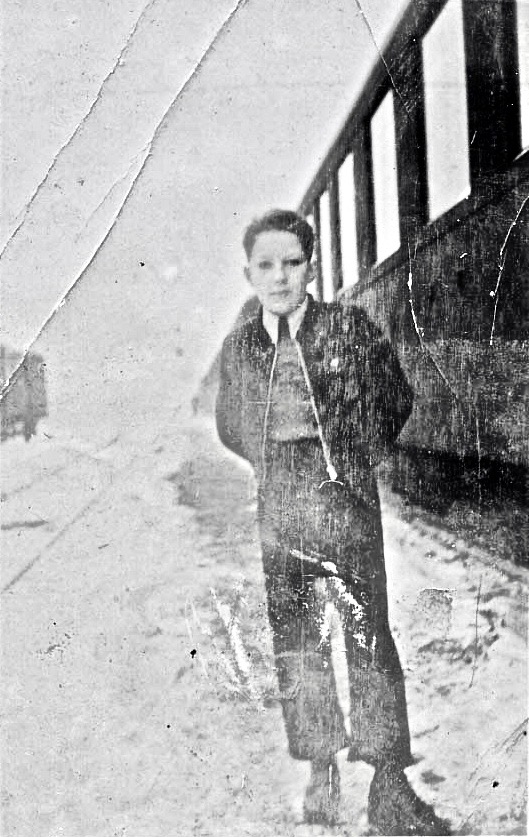

Hans and the others didn’t really know where Spain was; they only knew that it was in the south, and that there was a sea. His mother had prepared a little bundle for him with a crust of rye bread and cheese. As they boarded the train, the boys’ caregivers gave each child a plate, a spoon and a rough blanket.

Hans tugged at the string around his neck, from which a large cardboard card hung, with his first and last name, age, hair and eye colour, where he came from, and his mother’s name. The convoy began to move. Hans inhaled the charcoal coming through the top crack of the window as he watched his mother waving sadly at him from the snowy platform. Hans didn’t cry, but his stomach cramped like those times when he hadn’t eaten anything for days.

It would take several days to get there, the sea of Spain was far away, and to reach it they had to cross part of Switzerland, Italy and, mostly, France.

The nights were the most terrifying. Sometimes the convoy would stop violently, and the children would shudder at the flashing of the powerful lanterns on the roof of the carriage and in the windows. The caregivers reassured them that these were routine checks, and that everything was fine, but Hans only breathed when he heard the in-crescendo roar of the locomotive.

Hans and most of his fellows slept on the floor, but the younger ones were put on the luggage racks. They were so thin that, even if there were six bodies on the same rack, it did not stretch at all.

On 14 January 1950, the convoy of the seventh expedition of Austrian children arrived in Irún. More people waiting outside helped them down the tall metal stairs, and soon they entered a large hall where all kinds of fruit and strange food were laid out on large round tables with white tablecloths.

Hans was so excited that he wasn’t hungry at all, but a yellow and brown curved food that he had never seen before caught his eye. He looked around and saw that, little by little, the other children were beginning to take the food from the tables, while the people who had welcomed them waved their arms forward in encouragement.

He turned his neck from right to left once more, put his little index finger in his mouth, bit it, and took a step towards the table. He picked up the yellow food and decided to take a bite from the part that had no stem. Before he had finished the first bite, a lady shouted, «No, not like that,» and moved towards him, pulling her arm away from his mouth. Several men around him laughed sheepishly.

The lady took the yellow food out of his hand, and slowly uttered a few syllables:

– Plá-ta-no! Plátano! It’s very good, try it, but you eat it without the skin, look.

The lady pulled the stem and a long, curved, less yellow fruit appeared before her. She held out the banana and Hans prepared to sink his teeth into it.

– Go on, try it!

The reception in Irún was the first contact the children had with Spain. Hans thought that, at first glance, Spain was not very different from Austria, except that it was less cold and most of the people had dark hair.

When they had all finished tasting the food they were given and drinking some milk, they were told to get back on the train, as the journey continued to Pamplona, one of Spain’s large cities.

A few hours later, the locomotive was pulling into the Estación del Norte (Pamplona’s railway station), where a large number of people were crowded on the platforms and outside the station. Hans glimpsed camera operators in the distance recording everything that was happening in those moments of happy faces and emotion. (He did not know it yet, but the news of his arrival was picked up by NO-DO, a documentary film broadcast on cinema halls on Sundays across Spain). While he was fascinated by what he was seeing, nerves were getting the better of him, where would he go, what would his host family be like?

The next few hours passed very slowly, with many children leaving the halls of the religious institution where they’d been taken, and many others going to their new families straight from the station.

Hans was a shy boy, but on the long journey, he had had time to make friends with two other little boys from a Viennese neighbourhood far from his own named Helmut and Erik.

Night fell and the three of them were still waiting, not knowing where they would be taken. They were told that they would have to spend the night there, telling them that in the morning the train would leave for the south, to the city of Almeria.

Hours and hours on the train, the journey took so long that Hans, although not sleepy, slept most of the way. He only woke up once, when Erik and Helmut got off at Valencia station. The three boys, so used to goodbyes, held hands firmly, as they had seen the men of their families do.

Hans arrived at his destination in the early hours of the morning. Again he had to sleep in that place. He didn’t really mind too much, at least sleeping in a bed was better than sleeping on the wooden seats of the train. A few hours later, he was woken up and taken to the restroom to wash up. He was given new clothes and then went to the school nurse’s office for another medical examination. When he got into the car that would take him to his final destination, the reflection of the sun’s rays on the coloured tiles of the façade of the Almería train station prevented him from seeing the time clearly, but Hans, as he walked away, saw that it was 9 am.

He didn’t remember much of the car journey, as he was asleep most of the time. He had to close his eyes as the curves became more numerous and steeper, and he woke up as they were crossing a narrow bridge.

The town that was to welcome him was called Purchena, and the houses that stood before him were very different from the buildings in Vienna. They were all white and less tall, one or two storeys high. His house was in a small square.

Hans saw many people who seemed to be waiting for them at the entrance to the village, the arrival of the Austrian children generated much excitement.

Before meeting their families, the children went to mass after being received at the parish priest’s house. Finally, Hans met the members of his new family: Pepe, Rosina and Aunt Herminia*1. She was the one who picked Hans up and took him to the house in the little square. They walked up the steps and entered hand in hand.

Pepe shook his hand firmly and Rosina kissed him on the forehead. None of the three could believe that the family had just grown with the arrival of the little boy.

They knew that the journey had been long and tedious, so they put supper on early and took Hans to his room. From his bed, he could look out over the balcony at the full moon shining in the sky of Purchena that night of January.

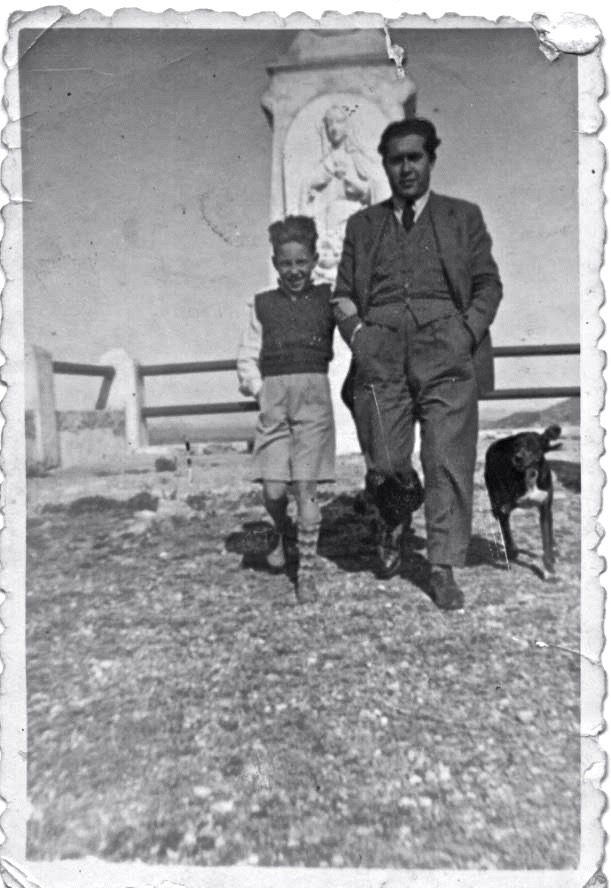

From the next day on, Hans’ life in Purchena was a complete adventure. He spent a lot of time with his adoptive father, who took him to the family cortijo, and to go hunting. There was nowhere they went without the dog Tundra, who became another of the boy’s faithful friends.

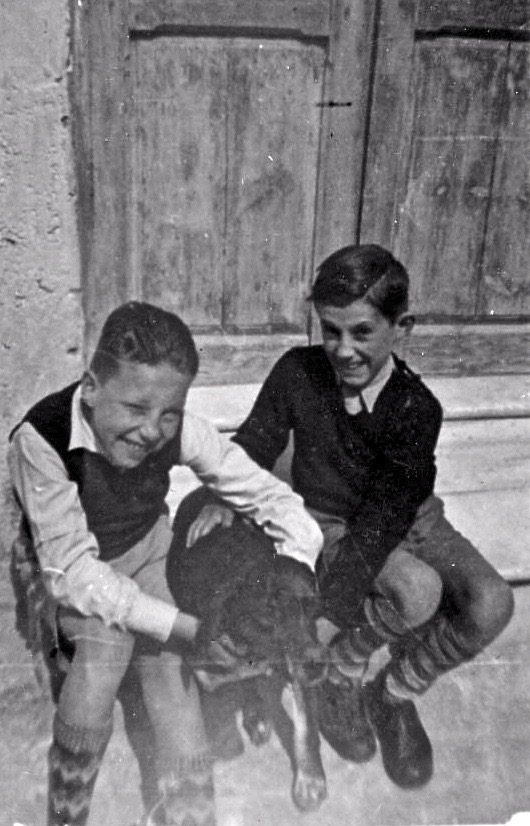

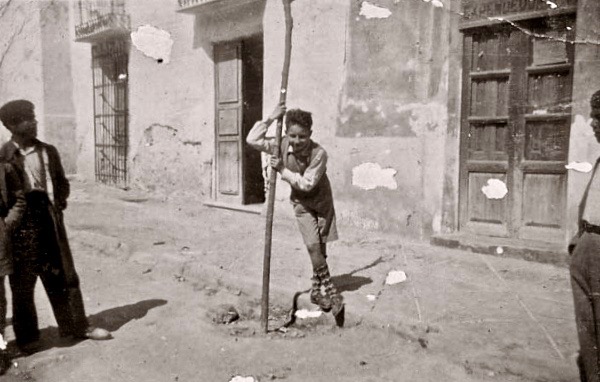

The days passed quickly between school and afternoon games. The gestural communication of the early days gave way to an increasingly better Spanish, which gradually eroded Hans’ native German, and he often found himself thinking to himself without finding the German words.

Hans made many friends at school and played with the boys in the nearby streets. The boy found himself in a new and different place, but he was not really homesick and adapted very well to living in Purchena. In fact, all the children fit in very well with their families.

January was left behind, along with February and March, and in April 1950 Hans celebrated his tenth birthday.

On 6 April, Hans and Pepe also went to the cortijo, and Hans felt like a real man. There was a donkey at the cortijo, and Hans wanted to climb on its back like the elegant riders he had seen on their horses. The donkey was smaller than a horse, so he felt he could ride it.

That was the only time Pepe scolded Hans.

– No, he can kick you!»- he shouted from inside the farmhouse. The boy didn’t understand the words, but he could imagine what they meant. He never again disobeyed his stepfather.

October came without warning. For days now Rosina had been sewing trousers for Hans with the scraps she had taken from her husband’s clothes, and she had several chain-stitched jumpers ready for him to take to his brothers.

In the house’s kitchen, there was a calendar in which Aunt Herminia crossed out the days every day at dinnertime. The first of October fell on a Sunday. After mass that day, Hans looked at the calendar for the last time. Aunt Herminia did not cross off the 1st that night, in fact, she did not cross off any more days until Hans’ departure.

None of them wanted him to leave, and the night before the big taxi that brought the children to Purchena was due to return, Hans tried to hide so as not to return to his native country.

He thought that the solanas were the perfect place to do so, behind a big jar in a corner. He stayed there for half an hour, until Tundra came up the stairs sniffing around his little friend. There was no escape: Tundra barked incessantly to alert his owners, despite the efforts of Hans, who waved his arms and hissed in an attempt to quiet Tundra.

The nine-month stay in Spain had come to an end. In tears, the family said goodbye to their child.

Hans blew kisses into the air to Pepe, Rosina, chacha Herminia and the many people who had gathered to bid farewell to the Austrian children.

Children who were now bathed in the southern sun, who had eaten all the dishes made with olive oil, and who no longer even missed butter.

*1 Members of the Guirao family have pointed out that the aunt’s name was Micaela (full name: Micaela Pardo Rojas). We have decided to include this note but also to leave the name Hans gave us in order to respect his testimony.

Author’s note: this story contains fictional components that have been added for the sake of the narrative and creative process.

Bibliography

• Un asunto de Estado: la acogida de niños austriacos en la geopolítica del primer franquismo, Lurdes Cortès-Braña, Doctora en Historia por la Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

• Los niños de la mantequilla. Historia de los 4000 niños acogidos en España tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Javier Más.

We want to express our gratitude to Dolores Galera, who has been the link and fundamental piece for reaching Hans. We hope you like this little homage to family Guirado, one of the many families in Purchena who touched the heart of children like Hans.

We are very grateful to Hans Schery, one of the children who lived in Purchena for 9 months. His contribution to this research is invaluable and we hope to be able to repay him for the happiness that talking to him has brought us one day. The following photographs are from his collection.

Clarita