Grippe

We are entering the final stretch of the year and it seems that we have to start taking stock, don’t you think? I have been doing it for more than four hundred years and I can assure you that there is no year like another.

Today I was thinking about my day-to-day life, about the daily lives of the purcheneras, about the Thursday market, with its churros and its street vendors who make that day of the week so enjoyable. And it has given me the urge to look back. How ironic, because travelling to the future is so easy for me. I always choose the past. It helps me to reflect and to see things from another perspective. To relativise things, to continue to have hope for what is to come.

I was thinking just today about the lapse of the last two years that paralysed the world and that caused us to wake up to a post-modern panorama. I won’t kid you, I don’t miss the confinements or virtually any of the events of 2021 or 2020 (minus my birthday, and the anniversary of the Moorish Games).

Travel restrictions were also put in place in the Council of Time, and the bowels of Purchena became boring as hell without visits from any of its regular travellers such as my good friend Abén or my godmother Brianda. And, fortunately, we immortals, the survivors of memory, do not have to suffer any of the sorrows of physical matter, although we well know that those of the soul can be even more painful.

By this, I mean that, in those two years which, although they are not distant, we want them to be far away, we were in no danger of contagion from the disease that terrified the world for months.

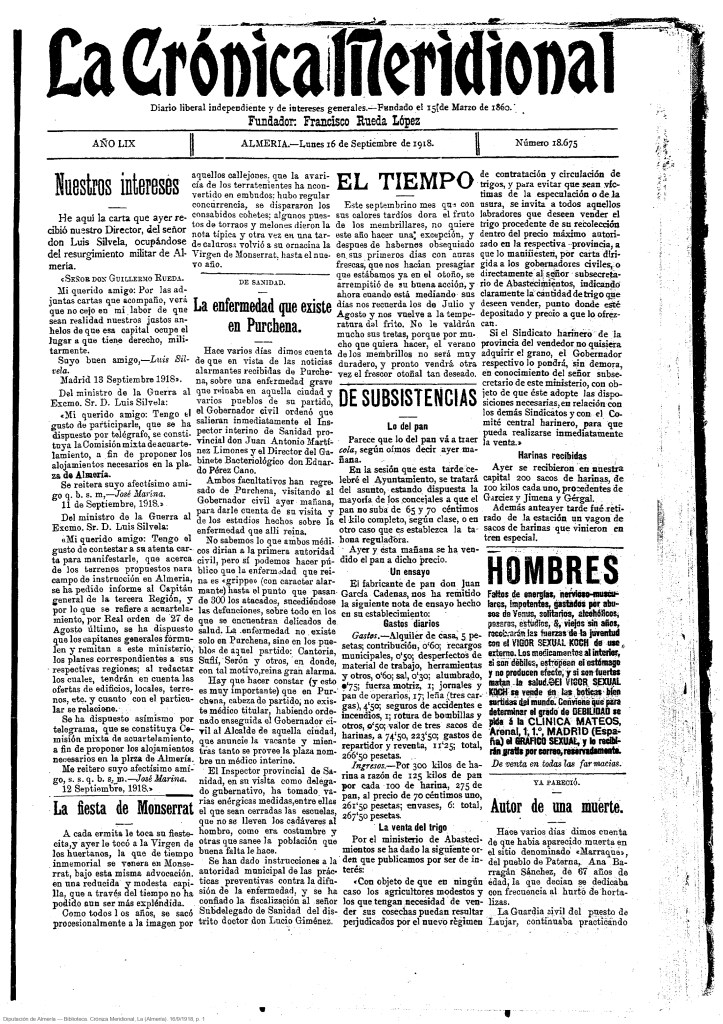

Nor were we during the last great pandemic: that of 1918.

It was September of that year when people began to fall ill suddenly and for no apparent reason. There were whispers in our village that the cause might be the water used to grow crops or a pest that had attacked the crops.

Terror gripped the families who saw all their members suffering from stomach ailments and high fevers, when the mothers, who cared for the rest, also fell ill and could not take care of their children or even their elders.

I remember wandering around Purchena with concern myself, as the people were really anxious and nervous. I perfectly remember the case of a family who lived in Calle La Manga. The woman of the house, Juana, was a widow. She had two small children, and the grandmother was also in the house. The first to fall ill was Juana. I knew it because I saw the children running down the hill to the square to look for help. Their mother had a high fever and there was no way to bring her down.

The next day, the grandmother was also in bed. I saw many neighbours coming up La Manga street with loaves of bread and woollen blankets. It was Friday afternoon and there were at least eight people in front of Juana’s house. Another neighbour had made some stew and was bringing some to the sick. She was the only one who entered the house, with the pot, the bread and the blankets: the others preferred not to go in. Sunday came and Juana’s little girl got sick too. Within a week, grandmother, mother and granddaughter had died. The boy was left an orphan.

For him, life would never be the same again.

On 16 September, the acting health inspector paid an emergency visit to our village to see the crisis state that prevailed here. Imagine more than 300 sick people in a village without a doctor. At that time, corpses were still carried on the shoulder; an unhealthy practice that was abolished, or at least recommended to be avoided, in the first days when the infection began to take hold, and which was called «grippe», with two pes.

Same as 13 March two years ago, public schools were closed and the streets and public areas of the town were sanitised to avoid contagion among the population. The prophylaxis adopted was washing mouths and noses, and disinfection of clothes and crowded spaces.

By 26 September 1918, there was already a shortage of medicines and food.

The worst affected part of the province was precisely the Almanzora Valley. The Spanish flu presented itself with intense abdominal pain and had no cerebral effects in the first instance; in the uncertainty and ignorance about it, it was thought to be typhus.

At the beginning of October 1918, Mr Ferret, who was now the provincial Health Inspector, stated in his official reports and in declarations to the provincial press that the situation was improving in our valley and that in a matter of two weeks the flu could be considered to have been extinguished in the epidemic villages, including Purchena. Let us remember that there was no doctor here. Doctors from the Beneficencia Municipal de Almería capital travelled here to take charge of a municipality plunged into panic and the darkest of circumstances that can devastate human beings: illness and death. The doctors Miguel de la Cára and Manuel de Villasante attended to the sick and those affected by the flu, in what the Health Inspector described as a «brilliant job».

Nevertheless, the number of deaths registered in Purchena in those last months of 1918 was 49, of which nine were children.

Let us think for a moment about what those 49 deaths would have meant in the first months of 2020. Undoubtedly a shocking number of human losses which, in a municipality such as ours, would have…

We purcheneros had a lot to thank those health professionals of 1918.

Now, let us go back to March or April 2020, when we all went out onto our balconies, terraces or windows to applaud the health workers for their great work in the gloomy scenario that was taking place in our country. An epidemic without precedent, without a vaccine. A virus, for some, with a clear Asian identity card, father Chinese Government, mother Wuhan laboratory test tube; a virus with the capacity to choose its occupant, how clever of the virus… Let us think of our neighbours commenting on the arbitrary order by which some were infected and others were not.

Let’s go back to those months when people no longer had faces, but hands that were either plastic-coated or irritated by the quantities of hydroalcoholic gel we put on them. And the saddest part: the deaths and human losses which, without a doubt, are always irreparable…

I remember those months as if they had been a bad dream. I don’t know if it happens to you too. This 2022 has been quite good to me and I have had some sweet moments again, especially in the last days of July, when I saw my dear people enjoying themselves so much with the XXI edition of the Moorish Games.

Maybe we don’t think so much of Covid anymore, or maybe we have forgotten or wanted to forget what those days were like; but in my house, my family always had at hand proverbs and sayings of popular wisdom, one of which perfectly exemplifies what I feel when I think of all those health professionals, the scientific community, and in short, those who worked in such difficult times, which says: «Even if you cannot afford to reward those who help you, at least make sure you are grateful to them».

I believe that all of us can do more than be grateful, and that is to make sure that all those who cared for us over these two years do not have to return to precarious and unfair working conditions.

Me, who only exist in the realm of thought and have no body, but who has already lived for many years, more than four hundred, tell you this.

Hugs,

Clarita

Author’s note: this story has been partially fictionalised from several news pieces retrieved from the National Library of Spain’ Archive.